India’s anti-obesity drug market has seen a sixfold jump in five years

The calls come thick and fast to Mumbai-based diabetologist Rahul Baxi – but not just from patients struggling to control blood sugar.

Increasingly, it is young professionals asking the same thing: “Doctor, can you start me on weight-loss drugs?”

Recently, a 23-year-old man came in, worried about the 10kg he’d gained after starting a demanding corporate job. “One of my gym friends is on [weight loss] jabs,” he said.

Dr Baxi says he refused, asking him what he would do after losing 10kg on the drug.

“Stop, and the weight comes back. Keep going, and without exercise you’ll start losing muscle instead. These medicines aren’t a substitute for a proper diet or lifestyle change,” he told him.

Such conversations are becoming increasingly common as demand for weight-loss drugs explodes in urban India – a country with the world’s second-largest number of overweight adults and more than 77 million people with Type 2 diabetes.

Originally developed to treat diabetes, these drugs are now being hailed as game changers for weight loss, offering results that few previous treatments could match. Yet their growing popularity has also raised difficult questions – about the need for medical supervision, the risks of misuse and the blurred line between treatment and lifestyle enhancement.

“These are the most powerful weight-loss drugs we’ve ever seen. Many such drugs have come and gone, but nothing compares to these,” says Anoop Misra, who heads Delhi’s Fortis-C-DOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology.

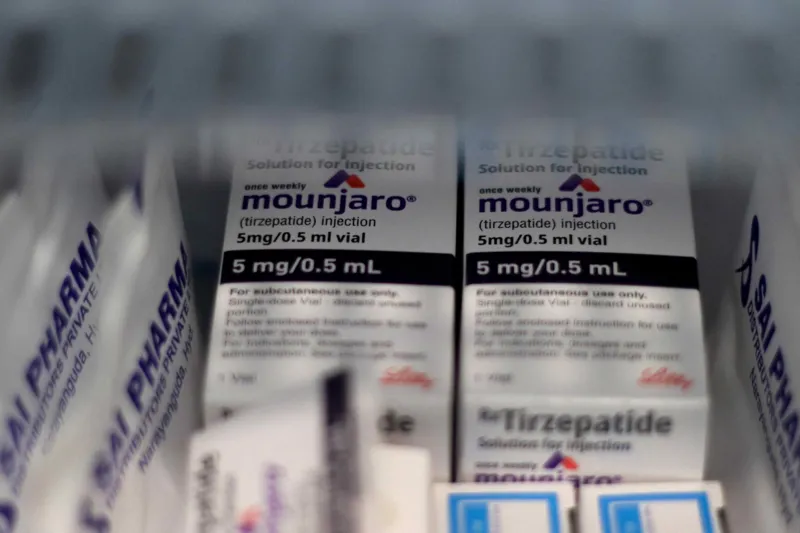

Two new drugs dominate India’s fast-growing weight-loss market. One is semaglutide, sold by Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk as Rybelsus (oral) and Wegovy (injectable) – while Ozempic (injectable) has been approved for diabetes in India but is not yet available for obesity. The other is tirzepatide, marketed by American drugmaker Eli Lilly as Mounjaro, primarily for diabetes but increasingly used for weight loss in India.

Both belong to a class known as GLP-1 drugs, which mimic a natural hormone that regulates hunger. By slowing digestion and acting on the brain’s appetite centres, they make people feel full faster and stay full longer. Taken once a week, most of these drugs are self-injected in the arm, thigh or stomach. They curb cravings – and in Mounjaro’s case, also boost metabolism and energy balance.

Treatment starts with a low dose that’s slowly raised to a maintenance level, and weight loss usually begins within weeks.

Doctors warn that most users can regain weight within a year of stopping, as the body resists weight loss and old cravings return. Prolonged use without exercise or strength training can also strip away muscle along with fat.

Also, not everyone responds to GLP-1 drugs, and most plateau after losing about 15% of their body weight. Side effects range from nausea and diarrhoea to rarer risks such as gallstones, pancreatitis and muscle loss. India’s high-carb, low-protein diet already fuels sarcopenic obesity – the loss of muscle alongside fat gain – and weight loss without adequate protein or exercise can make it worse.

“With all the media hype and social media buzz, these drugs have become something of a craze among affluent Indians eager to shed a few kilos,” says Dr Baxi.

The frenzy, a Delhi-based physician recalls, was evident even at a recent medical conference.

“Three months after the launch of a new drug, I’d treated about a hundred patients. A colleague said he’d done over a thousand – most using imported jabs bought on the black market.”

India’s anti-obesity drug market has surged from $16m in 2021 to nearly $100m today – a more than sixfold jump in five years, according to Pharmarack, a research firm.

Novo Nordisk leads the market with its semaglutide brands, with Rybelsus alone accounting for nearly two-thirds of the market since its 2022 launch, according to the firm. Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide (marketed as Mounjaro), launched earlier this year, had become India’s second-bestselling branded drug by September, according to Pharmarack. Each monthly injectable pen – four weekly doses – of these drugs costs between 14,000-27,000 rupees ($157–300), steep for most Indians.

What India has seen so far may just be the tip of the iceberg. Come March, the patent for semaglutide – the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy – expires here, potentially unleashing a flood of cheaper generics and making them more accessible. Jefferies, an investment bank, calls it a “magic pill moment” for India, predicting the semaglutide market could reach $1bn with the right pricing, uptake, and government incentives.

“What we have heard is that nearly a dozen companies are already ready with generic versions of Rybelsus, the oral drug,” says Sheetal Sapale, vice-president at Pharmarack. “But as affordability improves, the risk of misuse rises too.”

Doctors tell stories of patients being put on high dosage of weight-loss drugs by gym trainers, dieticians and beauty clinics with no authority to prescribe them. Some online pharmacies are delivering drugs after a cursory phone consultation in the absence of a prescription. Beauticians offer “bridal packages” promising rapid slimming before the big day. There are fears of spurious medicines flooding the market. Federal minister Jitendra Singh has “advised caution” on the new drugs.

“One patient asked me if these new medicines could help his daughter lose seven kilos before her wedding – in three months,” recalls Dr Bhaumik Kamdar, a Mumbai-based chest physician. “He wanted to know if they really work.”

One challenge in India, doctors say, is the way people perceive obesity – and how that shapes attitudes toward weight loss.

“Most don’t realise that obesity is a chronic, relapsing disease,” says Dr Muffazal Lakhdawala, a Mumbai-based bariatric surgeon. “Many people with chronic obesity try crash diets, lose some weight, then regain even more.”

“Here, if you’re overweight, people assume you’re well-fed and affluent. We’ve gone so far in avoiding the elephant in the room that we’ve normalised it.”

Obesity, doctors warn, is a gateway to a host of diseases. “It’s linked to at least 20 cancers, infertility, osteoarthritis and fatty liver – now one of the leading causes of cirrhosis,” says Dr Lakhdawala. Yet, despite it affecting nearly one in eight people globally, there’s still no universal consensus on how to define or classify obesity.

“The arrival of these drugs has changed the conversation – obesity is now being treated as a disease, not just a lifestyle issue.”

Doctors across specialities are now turning to weight-loss drugs for more than just obesity or diabetes.

Endocrinologists, diabetologists, cardiologists, and nephrologists are increasingly prescribing them to overweight patients to improve heart and kidney outcomes – for instance, those preparing for angioplasty or stenting.

Orthopaedic surgeons now prescribe them to help patients lose weight before knee surgery, while chest physicians use them for those with sleep apnea, a disorder that blocks the airway during sleep. “For patients with sleep apnoea who avoid using Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machines, these drugs can help by reducing weight, which in turn improves their sleep,” says Dr Kamdar.

Even bariatric surgery is evolving with India’s obesity boom. From just 200 procedures in 2004, the number soared to 40,000 in 2022 – a 200-fold rise.

Surgeons like Dr Lakdawala now run multidisciplinary programmes where patients on weight-loss drugs are first guided by endocrinologists, nutritionists, and psychologists for three to six months. “We don’t hand out drugs casually,” he says. “Those who don’t respond to the drugs or have severe obesity are then considered for surgery.”

His message to the growing number of urban Indians seeking quick fixes is blunt: “Don’t use the drugs for cosmetic weight loss – use it for life-threatening weight gain.”

And for those chasing quick fixes to shed just five or 10kg?

He has simpler advice: “Cut out sugar – it’s the biggest evil. Without that, no weight loss will last. Add four days of exercise a week, and you’ll lose those 5-7kg – no injections needed.”